In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

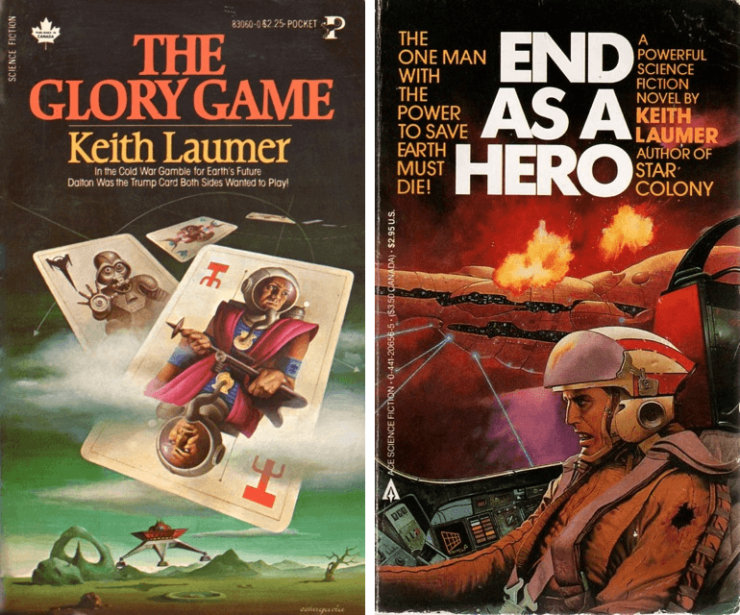

I recently decided it was time for me to revisit the work of the prolific (but always entertaining) Keith Laumer. I was torn, however, when preparing this column, trying to decide between two of his shorter novels. I decided to start both and then choose the one I liked best…but before I knew it, I had read them both right to the end. So, I decided to compromise by reviewing both works. They share the same theme of a determined hero doing their duty, despite the high costs, and the same rapid-paced narrative flow that never slows up. Yet they are also very different stories, and comparing those similarities and differences gives you a good sense of the range of this popular author, whose work was ubiquitous in his era.

When I started reading science fiction in the 1960s, a typical reader of SF was likely someone like my father: a veteran of World War II who worked in a technical or engineering field. Someone who remembered the excitement and absurdity of military life, and while they had adventures in their younger years, were now settled down into a more mundane suburban existence. But not settled down completely. They liked tales that offer some wish fulfillment, where the hero can punch a bully or an idiot in the nose when they deserve it, and stories willing to poke a little fun at senior military officers and bureaucrats. Adventures where a protagonist could stick to their convictions, and while they might suffer along the way, could end up on top. Where heroes were heroes and villains were villains. Short works that got right to the point, and told their story without wads of exposition. Stories they could read for a little escapism during their lunch hour as they enjoyed the contents of their lunchbox and thermos. The type of stories, in other words, that Keith Laumer is best known for writing. Today, I’m look at two of his short novels. The first is End as a Hero, a tale that first appeared in Galaxy Magazine in 1963, with an expanded version published in book form in 1985. The second is the novel The Glory Game, published in 1973.

About the Author

Keith Laumer (1925-1993) was a former U. S. Air Force officer and Foreign Service officer who became one of the most prolific science fiction authors of the late 20th Century. His stories were noted for their action, adventure, verve, and often for their humor.

I previously reviewed a collection of Laumer’s Bolo stories, tales of ferocious automated war machines, here, and that review contains biographical information on the author. Laumer was quite prolific, and wrote in a variety of subgenres, including tales of time travel and alternate worlds. His other famous series follows the career of an interstellar diplomat, Retief, whose stories are filled with adventure and humor in equal measures.

As with many authors who were writing in the early 20th Century, a number of works by Laumer can be found on Project Gutenberg. While those stories don’t contain The Glory Game, they do include the shorter version of End as a Hero that appeared in Galaxy Magazine in June of 1963.

End as a Hero

The book opens with Laumer writing in a sardonic tone, describing the home planet of the alien Gool as orbiting “the star known to medieval astronomer/astrologers as ‘The Armpit of the Central One.’” The Gool are a slug-like race with incredible mental powers, and they have detected the existence of humanity for the first time. In the brig of a naval spaceship a “Spaceman Last Class” (a rank that indicates Laumer has his tongue firmly in his cheek) has a bad dream, and on other ships, there are stories circulated of mental contact with strange beings. Terran Space Arm (TSA) ship Belshazzar is one of these ships, and scientist Peter Granthan is dispatched from the Psychodynamics Institute to investigate. He has developed remarkable powers to control his mind, and might be able to not only diagnose the problems experienced in the fleet, but even counter the activities of whatever beings are behind these problems. On their far-off planet, the Gool make plans to enslave humanity by controlling their minds. When Granthan arrives on Belshazzar, he finds the ship in chaos, and one of the crewmembers tries to kill him. On the messdeck, he is compelled to throw a coffee mug at a crewman and a brawl ensues; he ends up in the brig. During the incident, he senses alien minds at work. All sorts of crewmen are reporting strange events that aren’t possible, and while Granthan tries to convince them they are hallucinations, his influence never lasts for long. The events that follow are sometimes comedic, but it is very dark comedy, as more and more crewmen fall under the murderous influence of the Gool. The only thing I found improbable in the narrative is Granthan’s unexplained skill in hand-to-hand combat (something that a mention of prior military service would have addressed). Even the Captain attacks Granthan, only to end up committing suicide himself. Granthan builds a device to improve contact with the Gool, and soon finds himself battling for his sanity, and his very life, under their combined attack on his mind. The ship is destroyed, and Granthan is severely injured, but makes it to a lifeboat and heads for Earth.

As Granthan heads to Earth, we realize that contact with the Gool has transformed him—like the Gool, he has developed the power to affect other people’s minds. He has also figured out how to build a matter transmitter, and knows that in order to save humanity, he must infiltrate the supreme military headquarters and hook it up. This makes no sense, and as Granthan moves across the country, the reader realizes that we are dealing with an unreliable narrator, and is not sure whether to root for or against Granthan. He may think he is doing the right things for the right reasons, but that might all be a hallucination. Laumer’s work is sometimes surreal, and while I won’t reveal the ending, there are various twists and turns along the way. Once again, the fate of humanity comes down to the strength, wisdom, and determination of a single person.

I also went back and read the original, shorter Galaxy Magazine version on Project Gutenberg, and to be honest, ended up preferring it to the expanded version. It is much tighter and better-focused, and gets right to the theme of the tale.

The Glory Game

Captain Tancredi Dalton of the Terran Navy has just received designation as a Commodore and been assigned command of a flotilla in an upcoming show of Naval force on the border with space controlled by the Hukk, an upstart alien race that has begun challenging the Terrans for dominance. His girlfriend, Arianne, is the daughter of Senator Kelvin, and through her he gains some insight into the higher level politics roiling naval policy. The government is torn between Hardliners and Softliners: those who want to grind the Hukk into submission, and those who can’t believe that the Hukk, as rational beings, offer any threat at all. Dalton tells Arianne he doesn’t follow either line of thinking, but instead believes in “the Dalton line,” which is based on the world the way it exists, free of pre-conceived notions. At a local nightclub, Dalton sticks up for a table full of enlisted men, but then orders them out of the place when it appears they may start a brawl. He cares for the troops, but he is no pushover.

Dalton is then summoned to visit Senator Kelvin before he departs. The Senator tells him that Admiral Starbird, who leads the task force, has sealed orders not to fire on the Hukk under any circumstances, orders that come from Softliners who can’t imagine the Hukk making any offensive moves. But the Senator hints to Dalton that if he takes aggressive action before those orders are opened, he will be rewarded.

Buy the Book

The Last Emperox

A car comes to pick up Dalton, but he smells a rat and overpowers the minions sent to kidnap him. He then orders them to take him to their destination anyway. There, he finds Assistant Undersecretary of Defense Lair. It turns out that Admirals Veidt and Borgman have been issued sealed orders from Hardline elements in the Defense Department to take command of the task force and use it to make an unprovoked attack on the Hukk. Lair then gives Dalton his own set of sealed orders that allow him to take command of the task force, telling him to use them before Veidt and Borgman use theirs, and take action to avoid open hostilities with the Hukk. Dalton has been picked because he is headstrong and decisive, but Lair has failed to realize that he cannot expect such a man to toe his party line. Dalton is then cornered by a member of the Diplomatic Corps who wants him to spill the beans on internal Navy politics, but Dalton refuses to give him any information.

Dalton boards his flagship, a light destroyer, and heads out with his flotilla. He takes one of his ships and orders them to remain in the vicinity of Earth, with all their sensors operating. And sure enough, before he can join the main body of the task force, that ship detects an unidentified formation, heading toward the home planet. As Dalton suspected, it is an enemy formation, commanded by Admiral Saanch’k, one of the Hukk’s most capable combat commanders, capitalizing on the departure of the Terran fleet. Dalton guesses their goal is to seize the military installations on Luna, unseals his special orders, and tells the rest of the task force to continue with their mission. If he brings the entire force with him, the enemy will know their plan has been discovered too soon, so he must face the enemy vastly outnumbered. In a gripping action sequence, Dalton demands the surrender of the Hukk force. He suggests that there are Terran forces lurking nearby who can destroy the Hukks. They cannot wait for confirmation, and surrender their forces to him, as long as he promises them safe passage home. The Hardline Admirals attempt to take advantage of the situation and destroy the Hukk force, and only relent when Dalton threatens to fire on them. (If you don’t believe a smaller force can force a more powerful force to retreat by convincing them reinforcements must be nearby, you can read about the actions of Task Unit Taffy 3 during the WWII Battle of Leyte Gulf.)

In the aftermath, Dalton is a hero, especially to the Softliners, who welcomed his resolution to the crisis without bloodshed. He is promoted to Admiral and given a cover story to tell when he is summoned to testify in front of Congress. If he cooperates, his reward will be an assignment that will lead to a powerful political career. Instead he tells the truth, loses everything, including his girlfriend, and is assigned to operate a scrapyard on a distant planet. Eventually, when the Hukk decide to make that planet a beachhead for another incursion against the Terrans, Dalton gets one more chance to do the right thing.

The story has all the hallmarks of a typical Laumer story. The protagonist is loyal, selfless, brave and true. He is surrounded by venal and opinionated people who want only to acquire more power. He may face odds that seem impossible, and suffer along the way, but humanity depends on people like him. The story also offers an always timely lesson about the tendencies of political factions to retreat into their own bubbles, from which they search for information to validate their own biases, rather than seeking out facts and insights to help them truly understand the world in all its complexity.

Final Thoughts

Keith Laumer was known for books that were entertaining and easy to read, but also thoughtful and rewarding. There was always some useful medicine mixed in with his literary spoonfuls of sugar. In his long and prolific career, he sometimes repeated himself, revisiting themes and situations he had already addressed, but I never regretted picking up one of his books. The Glory Game and End as a Hero are solid examples of his work. Both are quality adventure yarns that keep you turning pages. End as a Hero gives us Laumer at his surrealistic best, keeping the reader guessing right up to the end. And while The Glory Game is pessimistic about the capabilities of human institutions, it is also a parable that underscores the importance of individual integrity and initiative.

And now I turn the floor over to you: Have you read The Glory Game, End as a Hero, or other tales by Keith Laumer? What do you think of his work, and what are your favorites? And what other adventure novels in science fiction settings have you enjoyed?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

I read the Retief novels and some of the Bolo tank ones when they came out. I enjoyed the political satire about the Cold War. I’d be very surprised, though, if most of his novels aged well for the newer generations of readers.

I’ve read The Glory Game, but I don’t think I’ve read End as a Hero. Standard action hero adventure is probably my least favorite mode of Laumer’s writing. I love his comedies and his more serious pieces with less action (many of the Bolo stories, for example). End as a Hero sounds as though it walks the line between standard action and deeper emotional piece.

Sadly, there is one Laumer novel I’ve regretted picking up: the aptly names Retief in the Ruins. It’s was written after his stroke, and it shows. Some of his other post-stroke work is still readable, but that alas was not.

Despite being in my 30s, I grew up with this style of pulp novel, churning through my Grandfather”s library (a WWII/Korea vet), before moving on to my Dads which was bits and bobs of early New Wave and a lot of Zelazny. A few years back I picked up a copy of “Worlds of the Imperium” thinking that a Laumer novel about parallel worlds might manage to tickle to nostalgic buttons at once.

For the most part I was disappointed. Laumer uses the science fiction set up to get to a pretty straight forward action story, with no scifi elements at all, before reintroducing them at the end for plot conclusion. It’s not necessarily bad, but I thought it dated pretty poorly. Campbell hyper-competent man as the hero, but without Heinlein’s (or, later, Scalzi’s) gift for characterizing them. Not a lot of flavor in the prose either, just wham-bam, incident to incident. Which was sad, because I read a few of the Retief stories, and while I’m not their target audience, it proves that the author could write funny.

Weirdly enough, I was halfway through the Shades of Magic series before realizing that while the stories are completely different, the worldbuilding is practically identical! It both makes me more disappointed – I can see so many things about Laumer to like (the worldbuilding here, the comedic voice there, the action elsewhere) but none of the individual stories worked for me.

Perhaps I should dig up the Bolo stories?

Don’t remember reading these. Read a lot of the Retief stories in the sixties but when I tried rereading them a few years back I was disappointed. They didn’t hold up well. Neither did Worlds of the Imperium.

The Glory Game sounds almost like an alternate world version of Retief where he went into the Navy instead of the foreign service.

I personally think pulp Laumer is the best Laumer. The kind of headlong dash into plot that works for shorter formats can get a little tiring when it goes on for the length of a novel.

My favorite Retief story is still “Diplomat-At-Arms”, with it’s portrayal of the aging Retief:

https://www.baen.com/Chapters/0671318578/0671318578___1.htm

I read a lot of Retief stories as a kid, introduced to me by my father who was also a foreign service officer and a fan of science fiction. The books would get a lot of re-reading since we were overseas with not much watchable television. Can’t say I’ve had the urge today to go back an read them again but this article makes me consider it.

@6 ssircar: Interestingly, “Diplomat-at-Arms” is the very first Retief story to be published. Everything else is just how he got there.

I have an essay kicking around in my subconscious about authors whose careers got derailed through no fault of the author. If it ever gets written, Laumer will be up near the top (maybe second to Doris Piserchia). He was clicking along nicely, carving out a nice little niche* for himself and then he had a debilitating stroke that damaged his ability to write without removing his need for the income writing brought him. There’s a five year hole in his novel output between The Glory Game and The Ultimax Man. As I recall, it’s possible to tell where he was in the MS of TUM when he had his stroke.

After the stroke, the only editor who seemed to be willing to publish Laumer was Jim Baen.

* Albeit one so infused with sexism even Spider Robinson protested, in his review of … Dinosaur Beach, I think.

@2 I recommend you give the magazine version of End as a Hero a try. There is no humor in that version, and it is a taut tale of suspense, where you don’t know who to root for until the very end.

@9 I always suspected that Baen’s purchase of Laumer’s later work was as much an act of charity as it was a business decision.

If only they’d had the idea of turning the Bolo books into a shared universe earlier.

@10: Actually, I flopped the books. I’ve read the original version of End as a Hero, and yes it was pretty good. As long as you don’t think about it too hard.The action Laumer that never seems to work for me is stuff like A Plague of Demons or A Trace of Memory. When there’s an emotional payoff, some question about what the hero’s doing or at least a leavening of humor, I still like he action stories.